This is an abridged extract taken with kind permission from:

Horseracing and the British, 1919–39

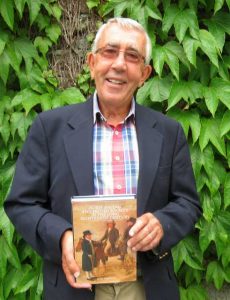

By Mike Huggins

Mike Huggins is Emeritus Professor of Cultural History at the University of Cumbria. His research interests, expertise and experience lie in the history of British sport, leisure and popular culture in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the opening up of a wider range of evidence for their study, including visual and material primary sources. Professor Huggins has written a number of books including Horse Racing and British Society in the Long Eighteenth Century

www.mikehuggins.co.uk

Stable Lads and Grooms

Stable lads and grooms were at the bottom of the ladder. They would come from all over the country. Their parents had a variety of backgrounds, often skilled or semi-skilled like coachman or joiner, some more middle-class. The parents of several were farmers. Stafford Ingham was the son of a Penge chemist. As many came from urban as from rural environments. Tommy Weston, for example, had been selling newspapers and working in a foundry. Most boys came to the stable on leaving school, with the key criterion being their light- weight build. Many were attracted by the apparent glamour of becoming a jockey, love of horses, and ideas of making money. Some already had brothers in racing, or came from racing families.

Most ambitious lads wanted to be jockeys, but only a few succeeded. Cyril Luckman suggested that ‘only one in a thousand’, Rickman that ‘one in a hundred’ became established jockeys. Some could already ride but this was not vital. Harry Wragg knew nothing about stable work and had never seen a race- horse when he arrived in Newmarket. Lengths of jockey indentures varied, most usually five years, but ranging from three to eight years. An initial ‘trial’ period was relatively calm. Lads did odd jobs and looked after ponies and hacks. Once indentures were signed they were often treated more harshly. Doug Smith had a ‘spartan and cheerless’ apprenticeship near Wantage, which he described as ‘very tough’, with strict physical discipline. Stable food could be poor. Lads soon learned to keep quiet and be civil, addressing head lads, jockeys and other senior figures as ‘Mr’ rather than using first names. New lads were often the butt of practical jokes: water-buckets on top of a door or loosened bed frames. Stable initiation rituals, usually involving greasing and chaffing of genitals, conferred their racing nickname and supposedly qualified them to learn the finer points of horsemanship.

In stables lads lived in dormitories, accommodating from three or four up to thirty. Older ‘board wagemen’ out of apprenticeship lived in. Married men lived out and came in from their homes. Most earned around £2 a week if married, though less if single. Winning owners sometimes gave presents to the stable lads who ‘did’ their horses, which for a lucky few increased their earnings. Each trainer negotiated wage settlements separately, and lads’ wages were tradition- ally very low, although most lived in at the stables, so accommodation and meals were free, and any doctors’ bills were paid. Doctors’ bills were necessary, since injuries were common: horses bit, kicked or threw their riders. One ex- jockey, Tom Aldridge, died at Durdans when his horse shied at some donkeys.

Lads commonly took care of two horses, and occasionally three, once they proved reliable. They were wakened by the head lad somewhere between five and half past six, and began by cleaning out the boxes and stalls. Wooden skips or sacks would be used for ‘mucking out’. The horses were ‘dressed over’, vigorously strapped with wisp and rubber, and got ready for riding out with the rest of ‘the string’ or first ‘lot’ from six to seven o’clock. Then lads might have a slice of bread and a cup of tea. Tack would be put on, and horses sheeted up. Trainers would accompany the string to the gallops to supervise exercise, usually from hacks, thoroughbreds or trap, while wealthier trainers sometimes used cars. Gallops lasted up to an hour and a half on nearby laid-out heath or moorland. Usually two days were ‘fast work’ or galloping days, over the horse’s best distance. Trainers would vary training according to a horse’s characteristics, habits, condition and feeding, drawing on their experience and practice. Too much work would lead to poor eating. On the other days only trotting and cantering were required. Back in by nine, horses would be groomed over, boxes set fair and the horses fed, and lads would get breakfast. A second lot would be turned out by around quarter to eleven, and would be back in and done up by twelve thirty, unless it was wet, when they would have to be dried off. Older grooms would often be given time off in the afternoon, but at many yards apprentices would clean windows, weed, sweep and tidy the yard and drives, crush corn and cut chaff, and do odd jobs like tack and brass cleaning or washing out saddle rooms. Evening stables were around half past four.

The full book is available to read free of charge on OAPEN – the online library and publication platform. Photographs from other sources.

The work is protected by a Creative Commons licence: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)