Thank you to Sue Cocker for sharing this valuable information

In the days before the Welfare State, being unable to work meant poverty. The poor could look for help from charity or the Parish (ie the organisation headed by the local church, not the more modern civil Parish Council) In Lambourn, the Isbury Almshouses had since the 15th century, cared for a few men of good character and there were other charitable foundations – Hardrett’s Almshouse, Christina Organ’s bequest or Poors Furze in Eastbury – which also helped. Since the mid 16th century the Parish had been given increasing responsibilities for the care of the poor. Parishes could raise a Poor Rate, or local tax, and pay out money or give out goods to parishioners in need in their own homes (indoor relief). In 1710, Lambourn Vestry (the committee concerned) handed out over 46s weekly (£2.30). Examples of what was paid include: 3d for Nathaniel Pantry of Lambourn for his house rent; 1s for Widow Patey, of Lambourn Woodlands, lame and aged; 6d for Mary Vize, towards bringing up her bastard child.

Parishes had a duty to “set the poor on work”, either by arranging apprenticeships, finding local work (often mending local Parish roads), or buying materials for the unemployed to turn into saleable goods. They could, if they wished, build a poor- or work- house. This was often an existing house, converted to provide shelter, storage space for materials and a place to work for a few people. The remote community of Lambourn did have a poorhouse, but we have few details of its origins. We do know that in 1832, it housed 7 males, aged 85, 76, 68, 38, 13, 10 and 5 months, and 15 females, aged 88, 67, 64, 54, 41, 33, 32, 27, 23, 22, 19, 16, 14 and 8. The ages give us a rough idea of how the workhouse was used at this time.

This system of Parish-based relief worked well for many years, but as the population rose in the 18th century, it came under severe pressure. All over the country, parishes were having to raise additional Poor Rates. Lambourn was no exception – most years there seem to have been 3 or 4 rates levied on property owners and once 7 were demanded. The rate payers were, understandably, not happy! Parishes became much stricter about who could claim the scarce resources, so that “the idle poor” (today we would call them “benefit scroungers”) could not live off the Parish. A child born in a Parish had a claim on it, and there are stories of heavily pregnant, unmarried paupers being driven out of parishes so that the child would not be a charge on the parish funds. Locally things were made worse by the introduction of the Speenhamland System, devised by Berkshire magistrates at a meeting at the Pelican, Speenhamland in May 1795. Magistrates (usually local landowners) set agricultural labourers wages. The Speenhamland System linked wages to the cost of a gallon loaf (8lb 11oz). Depending on the cost of a loaf and the number of children a man had, they set a weekly wage. (e.g. if a loaf cost 1s, a single man’s wage should be 3s per week. If he had 4 children, his wage should be 10s 6d.) If his employer could not afford to pay all the wage, then the labourer could claim the rest from his Parish. Since the price of bread (and the number of children) fluctuated, employers often couldn’t (or wouldn’t) pay the full wage. Thus men who were in full employment and who prided themselves on being industrious and able to support their families through their toil, felt humiliated when they had to go, cap in hand, to the Parish. The system was widely adopted and continued for over 30 years, until poor harvests, a bad winter, fear of rising unemployment and the introduction of new agricultural machinery triggered the so-called Swing Riots in the south in 1830 -1. Men from this area were involved in destroying farm machinery and attacking farms. The government, unnerved by the riots and facing taxpayers protesting about rising poor rates, decided to reform the Poor Law.

In 1832 a Royal Commission was set up to investigate provision for the poor. A questionnaire was sent to prominent local inhabitants (magistrates, overseers of the poor, vicars) asking them to give information about the state of their parishes, especially about relief given to the able-bodied poor. Henry Hippesley, of Lambourn Place, answered for Lambourn. His answers included the information that there were “some large landowners, a good many small farmers” and the land “is generally speaking less highly cultivated than in former times. I do not consider there is any superabundant population though many are unemployed for want of money to pay them” . “The usual food of labourers families is bread, butter, cheese, bacon and potatoes and with some tea, but they seldom have fresh meat” In the week before the arrival of the questionnaire, 500 people received relief. This did not include those eligible for an allowance according to the Speenhamland System, which seems to have been able-bodied labourers with more than 2 children. The 1831 census gives the population of the Parish as 2,386, so about 20% of the population was claiming some form of relief, which added up to an annual bill of £2,350.

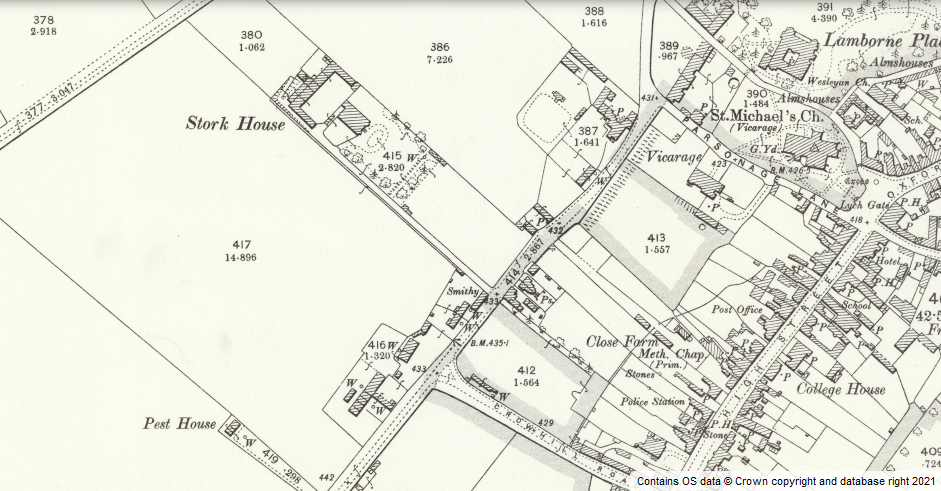

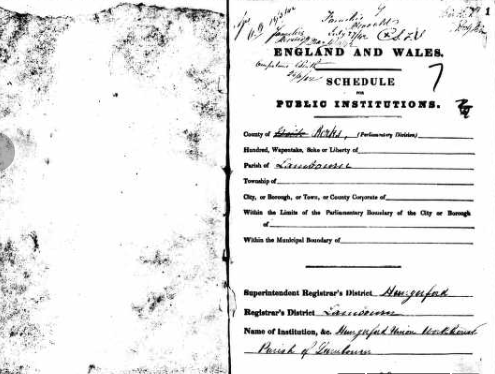

Following the Commisioners’ Report, the government rushed through the New Poor Law in 1834. This was intentionally harsh on the “idle poor” – those who were able to work, but who, in the eyes of the authorities, chose not to. The law made no allowances for lack of employment in an area, either seasonally or longer term. All those who claimed relief were supposed to enter a workhouse, where conditions were deliberately harsh. Indoor relief was to stop. Men, women and children were separated. All had to work at whatever the Master of the Workhouse set them to do, children were apprenticed, often to the labour-hungry factories in the North, inmates wore workhouse uniform and were fed an unappealing diet. Parishes were grouped together in Poor Law Unions. Lambourn was part of the large Hungerford and Ramsbury Union. As Lambourn already had a poorhouse, it was decided to expand it in line with the new law. By September 1835 the extensions were complete, including “proper bars” being fitted to the windows of the workroom. (Not for nothing were the new workhouses referred to as “bastilles”.) The total cost of the refit was £1736. 9s. We don’t know what the building looked like, but it is unlikely to have been as grim, or as large, as those in towns. There were standardised plans for workhouses and a rural model was available, but how far Lambourn’s version was new, or if it just adapted the existing building, isn’t clear. The tender was for “alterations to Lambourn workhouse”, but the final invoice says £1539.3s. 6d was paid for “building the poor house”, whilst an additional £59 17s was included for “repairs”.

The minutes of the local Poor Law Union Board of Governors show that, in May 1835, a master and matron (Mr and Mrs. Ayres or Ayers) had been installed and were to be paid £100 per annum, with “use of the front garden, rent free, and the labour of the paupers (the official term for those claiming relief) to cultivate it”. Mr & Mrs Ayres were allowed 17lbs of bread, 6lbs of meat, 2lbs of cheese, 1.5lbs of butter, ¼ lb tea, 2 lbs of sugar, plus salt and pepper per week, as well as 6 bushells of malt and 6lbs hops annually. A pauper in their care had 5lbs bread, 10.5 pints gruel, 1lb beef or bacon, 1.5 lbs potatoes, 4.5 pints soup, 14 oz suet pudding, ½ lb cheese and 4.5 pints broth per week. Tea was only given to the aged or infirm.

The minutes reveal snippets of what life was like in the workhouse. Visiting paupers in the workhouse was restricted to Mondays and Fridays, up to 6 p.m. 9 men – Messrs Bradley, Dobson, Dobson, Faithful, Hamblin, Hobson, Pike, Pocock and Sopp – who refused to work were deprived of meat on the next day. Withholding meat was a standard punishment. In July 1841 Mary Ann Petit destroyed Union clothes and was not given meat for a week. Perhaps she was rebelling against the regime by destroying her uniform, or perhaps she had torn her clothes by accident – her side of the story is not recorded. The 1841 census shows Mary Ann was 14, in the workhouse “without parents”, but with a younger sister and brother. Perhaps the little family had been taken in under the Board’s ruling that in the case of poor persons in employment with large families, the Board would be empowered to afford relief by taking one or more of the children of such poor persons into the workhouse of the Union.

Another entry, in August 1836, authorises Mr Ayers to take out a summons against Widow Carter for deserting her children in the workhouse. Two chemise and 2 shirts were ordered to clothe the Carters children. It seems likely that this was the family of John Carter, who was hanged for arson in 1832.

The New Poor Law supposedly stopped Outdoor relief – all relief was to be given in the workhouse, but the local authorities obviously realised this was not always practical. The “two imbecile children” of Richard Lewington were to have 2s 6d and two loaves. Rachel Aldridge, whose husband had been transported, and who had 3 children, was given 2 loaves at 2s per week – clearly they were not in the workhouse. Perhaps Rachel had work but just needed a helping hand. More in the spirit of the law, Elizabeth Mabberley was offered 1s. “or workhouse”. Was she being given a warning, or had she too got a job?

The harsh workhouse regime was intended to dissuade anyone from asking for relief. Life inside could be made even more intolerable by a corrupt administration, as shown in 1847 by the Andover Workhouse case, where the Master appropriated the money intended for the food for the inmates and the paupers were found to be starving. Mr Ayers does not seem to have been corrupt, but in July 1841 a pauper from Kintbury, Anna Maria Brunsdon, claimed he was the father of her child. The Governor’s investigated, but no more was reported and Ayers kept his job.

On a lighter note, in July 1841, it was reported that “considerable damage had been done to the vegetables in the workhouse garden by Mr Child’s cow and the Board ordered the Clerk to write to Mr Child and say that if he did not prevent the cow from trespassing in future the Board would be obliged to take proceedings against him.”

Lambourn’s workhouse was closed down sometime between 1847 and 1851. The inmates were moved to Hungerford, a much larger building, which some of you may remember as Hungerford Hospital. For paupers in Lambourn, the threat of removal to Hungerford must have added to the harshness of the workhouse regime.

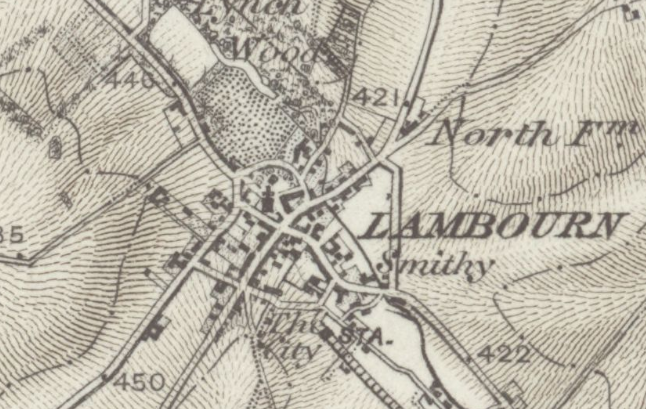

Eventually, the welfare reforms of the 20th century removed many people from the scope of the Poor Law and it finally ended in 1947, with the coming of the Welfare State. Meanwhile, the site of Lambourn’s workhouse had become (what else in Lambourn) a successful racing yard – Stork House.

According to the 1841 census, those living at the Workhouse were approximately 40 adults and 97 children (under 18)

Liz Beard 2021

I have written a document (11 pages) which has some details of the staff and inmates of the Workhouse on the 6th June 1841. I’ve managed to find out which parishes in the Poor Law Union they came from, as well as details of some baptisms, burials and marriages for a number of them. Also a little information on the the Workouse set-up pre-1841 which might add to Liz’s article.

If it’s wanted I can (try to) provide a PDF version of my document

Hello Michael, that certainly interests me and would love to include it. If you would kindly send to me direct at lizbeard@hotmail.co.uk that would be great. Either word document or pdf.

Many thanks. Liz